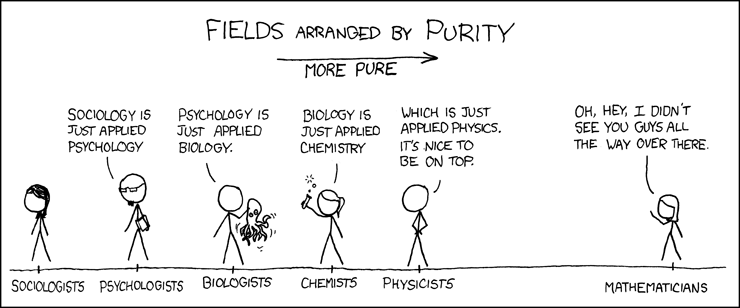

There seems to be a consensus among certain academics that science is grounded in mathematics and that math is the “purest” of all disciplines, reliant on no other field than itself. There is math and there is applied math; it encompasses every other scientific discipline. This comic from XKCD sums it up nicely:

From this assumption it becomes easy to see how the dichotomy of religion versus science becomes so easily accepted by both sides of the debate. Anything that does not have mathematics as its foundation must therefore be unscientific. Religion and philosophy might make for nice personal beliefs that make us feel good about ourselves but they aren’t objective and they can’t tell us anything about the world that science couldn’t already explain.

Famed physicist Stephen Hawking elaborates:

Most of us don’t worry about these questions most of the time. But almost all of us must sometimes wonder: Why are we here? Where do we come from? Traditionally, these are questions for philosophy, but philosophy is dead. Philosophers have not kept up with modern developments in science. Particularly physics. Scientists have become the bearers of the torch of discovery in our quest for knowledge.

In fact, I argue the contrary. Science, including the science of mathematics, ultimately find their foundation in philosophy. Disciplines like logic and epistemology provide the basic building blocks upon which the scientific method and mathematical proofs are built.

Albert Einstein is a perfect example of how philosophy informs science. Einstein would often spend time simply thinking through problems, reflecting not merely on its empirical aspects but on concepts and the meaning behind the empirical evidence. As an article by PBS entitled Why Physics Needs Philosophy notes: “Einstein arrived at the theory of relativity by reflecting on conceptual problems rather than on empirical ones.” In other words, philosophy played a key role in developing the theory of relativity.

An excerpt from an interview with physicist George Ellis further elaborates:

Horgan: Krauss, Stephen Hawking and Neil deGrasse Tyson have been bashing philosophy as a waste of time. Do you agree?

Ellis: If they really believe this they should stop indulging in low-grade philosophy in their own writings. You cannot do physics or cosmology without an assumed philosophical basis. You can choose not to think about that basis: it will still be there as an unexamined foundation of what you do. The fact you are unwilling to examine the philosophical foundations of what you do does not mean those foundations are not there; it just means they are unexamined.

Actually philosophical speculations have led to a great deal of good science. Einstein’s musings on Mach’s principle played a key role in developing general relativity. Einstein’s debate with Bohr and the EPR paper have led to a great of deal of good physics testing the foundations of quantum physics. My own examination of the Copernican principle in cosmology has led to exploration of some great observational tests of spatial homogeneity that have turned an untested philosophical assumption into a testable – and indeed tested – scientific hypothesis. That’ s good science.

Physicist and quantum gravity expert Carlo Rovelli argues that this philosophical superficiality has actively harmed scientific advancement.

Theoretical physics has not done great in the last decades. Why? Well, one of the reasons, I think, is that it got trapped in a wrong philosophy: the idea that you can make progress by guessing new theory and disregarding the qualitative content of previous theories. This is the physics of the “why not?” Why not studying this theory, or the other? Why not another dimension, another field, another universe? Science has never advanced in this manner in the past. Science does not advance by guessing. It advances by new data or by a deep investigation of the content and the apparent contradictions of previous empirically successful theories. Quite remarkably, the best piece of physics done by the three people you mention is Hawking’s black-hole radiation, which is exactly this. But most of current theoretical physics is not of this sort. Why? Largely because of the philosophical superficiality of the current bunch of scientists.

The “why not?” philosophy is readily observable today. The article Quantum Physics and the Abuse of Reason illustrates the rabbit hole many physicists have gone down based on their interpretation of a single experiment. The double slit experiment shows light behaving both like a wave and a particle, which is strange in itself, but weirder still the light’s behavior seems to change under observation. Unobserved the light behaves both like a wave and a particle but under observation the wave-function collapses. There are many theories attempting to explain this phenomenon. Some people believe that the double-slit experiment proves that the universe is not an external reality but that it is our conscious observation that determines the universe. Others believe in a “many-worlds” theory that states that “the wave-function never actually collapses, it only appears to collapse, because reality itself splits into two channels. Our consciousness only resides in one of these worlds at a time, so that’s why we can’t perceive or interact with these alternate realities. Because quantum events happen constantly, you end up with a practically infinite number of real universes, each with only a micro-change between the others.”

Some are willing to throw out classical mechanics based on an experiment we don’t fully understand. Other scientists are abandoning the idea of “falsifiability.” The concept refers to whether something is falsifiable or testable. For example, a universal generalization like “all roses are red” can’t be proven by any number of confirming observations but it can be falsified by observing a single rose of another color; it is therefore falsifiable. Falsifiability has long been the demarcation between science and non-science where the practice of declaring an unfalsifiable theory to be scientifically true is considered pseudoscience. We cannot declare true what is untestable. However, according to physicist Sean Carroll falsifiability is a philosophical concept with no place in modern physics. String theory is unfalsifiable in practice, at least for now, but Carroll believes that that shouldn’t deter us from accepting it as a legitimate theory on the same level or even preferable to testable alternatives. Why not?

Ellis explains why not:

This is a major step backwards to before the evidence-based scientific revolution initiated by Galileo and Newton. The basic idea is that our speculative theories, extrapolating into the unknown and into untestable areas from well-tested areas of physics, are so good they have to be true. History proves that is the path to delusion: just because you have a good theory does not prove it is true. The other defence is that there is no other game in town. But there may not be any such game.

Scientists should strongly resist such an attack on the very foundations of its own success. Luckily it is a very small subset of scientists who are making this proposal.

To physicists like Ellis and Rovelli philosophy is far from dead and is in no danger of being outpaced by science. To the contrary, good science depends on good philosophy. Any attempt to push philosophy out of the realm of science will only be met with scientific disaster. A scientific community stripped of all philosophical tendency would be a stale, stagnant beast, resistant to truly novel ideas while accepting the latest fad theories with utter gullibility. Now that would be a shame.